Surveying Voters on Election Denialism

These surveys were conducted before the election, in August and September, shedding light on why voters rejected Election Denier candidates when they went to the polls.

In This Resource

-

The election denial movement is unpopular.

-

The voters who often swing elections really don’t like election denial.

-

Voters reject violence, threats, and lies.

-

The more voters learn about Election Deniers, the less popular they are.

-

Methodology

-

Details on language used in information provision experiments

A project of States United Action

Why did Election Deniers fail so thoroughly in the midterm election? Which types of voters rejected Election Denier candidates, and why? States United Action conducted statewide-representative polls of registered voters in Arizona, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin that help answer this question. These surveys asked respondents about a variety of democracy-related questions, including their attitudes toward Election Deniers.

These surveys were conducted before the election, in August and September, shedding light on why voters rejected Election Denier candidates when they went to the polls.

Here’s what we learned.

The midterm elections weren’t a fluke, or the result of a one-off slate of candidates who couldn’t connect with voters. Our poll suggests that in the midterms, the election denial movement itself played a big part in dooming these campaigns.

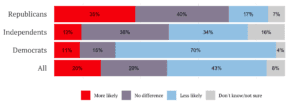

We asked respondents how they would feel about a candidate who believed the 2020 election was stolen from Donald Trump: Would they be more likely to vote for such a candidate, less likely, or would it make no difference? A plurality of all voters across the four states (43%) said they would be less likely to vote for an Election Denier.

Elections often come down to voters who aren’t attached to either major party and those who vote inconsistently. In our polls, both of those groups rejected Election Deniers at high rates.

Among Independents, 34% said they would be less likely to vote for an Election Denier, compared with only 12% who would be more likely.

Figure 1: Vote for Election Denier by Party Identification

“If a political candidate for office says they believe the 2020 presidential election was stolen from Donald Trump, would that make you more likely to vote for that candidate, less likely to vote for that candidate, or would it not make a difference in your vote?”

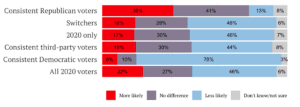

Inconsistent voters felt much the same way. Among Americans who sat out the 2016 election but did vote in 2020, the most common response was that they’d be less likely to support an Election Denier. That was also true for voters who switched the party they supported between 2016 and 2020.

Figure 2: Vote for Election Denier by 2016 and 2020 Vote Choice

Graph only includes respondents who reported voting in 2020.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that the voters who so often decide elections—those voters without attachments to either of the two major parties, or those who vote inconsistently—rejected the Election Denier movement at high rates.

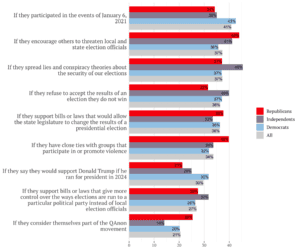

We wanted to know what specifically voters dislike about Election Denier candidates. So we asked them about nine behaviors that Election Deniers have engaged in. Voters said they were most concerned if candidates participated in the January 6 insurrection (41% of respondents selected this option), encouraged people to threaten election officials (37%), or spread lies and conspiracy theories about our election system (also 37%).

While Democrats and Republicans each selected a top three concern that was not shared by other partisan groups—Democrats chose a candidate’s participation in January 6th as their top concern, and a top concern among Republicans was a candidate’s support of bills that would allow the state legislature to change the results of a presidential election—both Democrats and Republicans shared some top concerns chosen by Independents. Both Democrats and Independents reported an Election Denier candidate’s spread of lies and conspiracy theories and their refusal to accept an election loss as two of their top three biggest concerns. Independents and Republicans also had something in common—both groups selected an Election Deniers’ encouragement of threats toward elected officials as a top three concern. Another top three concern selected by Republicans was if a candidate had ties to groups with a history of violence. It appears that Republicans who are averse to election denialism are particularly concerned by a candidate’s incitement of violence or proximity to violent political extremism.

Figure 3: Concerns about Election Deniers by Party Identification

“Below is a list of concerns that some people have voiced about the behavior of candidates who say they believe the 2020 presidential election was stolen from Donald Trump. From the following list of behaviors, please choose three (3) that you believe are most concerning in a candidate.”

Question was asked only of those respondents who reported being “less likely” to vote for an election denier. Bars represent the percentage of respondents who selected an option as one of their top three concerns.

When voters in the poll were given more information about a hypothetical candidate’s Election Denier activity, they were more likely to express an unfavorable opinion of that candidate.

To test the possibility that some respondents’ reported indifference toward Election Denier candidates could be explained by a lack of knowledge about the kinds of behaviors these candidates have engaged in, we conducted a series of question wording experiments, providing information to some respondents while withholding it from others. All respondents were asked to rate their favorability of a candidate who has questioned the results of the 2020 election. However, we provided information highlighting a candidate was an Election Denier—in the form of a short sentence describing their election denial activities or statements—only to a random half sample of respondents. The other half of respondents did not receive any information indicating the candidate was an Election Denier.

In the full sample, respondents who received additional information were 14 percentage points less likely to say they “haven’t heard enough” and 14 percentage points more likely to express an unfavorable opinion of an Election Denier than those who did not receive the additional information. Among Independents, additional information reduced “haven’t heard enough” responses by 17 percentage points and increased unfavorable opinions by 24 percentage points. While additional information similarly reduced “haven’t heard enough” responses among Republicans, the change was roughly half of what it was for Democrats and Independents (just nine percentage points). Furthermore, providing this additional information caused Republicans to polarize in their opinions of an Election Denier candidate: among those who received additional information, unfavorable ratings increased by four percentage points while favorable ratings increased by the same margin.

Figure 4: Results of Information Provision Experiments by Party Identification

For more details about specific question wording, click here.

Taken together, results from our surveys shed some light on voters’ perceptions of Election Deniers during the 2022 midterms. The poll results help explain the election results. Election denial simply wasn’t a viable strategy. It received little support from people who hold no attachments to either of the two major parties and from inconsistent voters—precisely the types of voters who so often decide election outcomes. People reported disliking Election Deniers for a wide variety of reasons, and for the most part, the more they learned about Election Denier candidates, the less they liked them.

The lesson: It’s not just bad for our democracy, it’s bad politics.

Prior to the 2022 midterm elections, States United Action worked with Citizen Data to field statewide-representative polls of registered voters in four states: Arizona (n=2,412), Michigan (n=2,422), Pennsylvania (n=2,378), and Wisconsin (n=2,175). These text-to-web surveys were fielded between August 23rd and September 6th, 2022. The margins of error for each poll were ± 2% in each state except for Wisconsin, where the margin of error was ± 2.1%. Responses were weighted by YouGov to match the population characteristics of each state with respect to race, education, gender, age, and vote choice in the 2016 and 2020 presidential elections.

In keeping with best research practices (e.g. Keith et al. 1992), the partisan breakdowns included in this report classify those Independent voters who reported “leaning” toward either the Democratic or Republican parties as partisans. Therefore, the “Independent” category reported above includes only those Independents who professed no party attachments whatsoever.

- Arizona experiment: As you may know, Mark Finchem is a member of the Arizona House of Representatives who is running as a candidate for Secretary of State of Arizona in this year’s election. [Treatment language: He was present at the events at the Capitol on January 6, 2021, and he continues to call for the results of the 2020 election to be overturned.] How favorable of an opinion would you say you have of Mark Finchem, or haven’t you heard enough about him?

- Michigan experiment: As you may know, Matthew DePerno is an attorney who is running as a candidate for Attorney General of Michigan in this year’s election. [Treatment language: DePerno has met with members of former President Donald Trump’s administration to work on a plan to overturn the results of the 2020 election and continues to spread lies and conspiracy theories about that election.] How favorable of an opinion would you say you have of Matthew DePerno, or haven’t you heard enough about him?

- Pennsylvania experiment: As you may know, Doug Mastriano is a member of the Pennsylvania State Senate who is running as a candidate for Governor in this year’s election. [Treatment language: His campaign paid for buses to send over 100 supporters of Donald Trump to D.C. to participate in the events of January 6, 2021, and he continues to spread lies and conspiracy theories about the 2020 election. If elected governor, Mastriano would have the power to appoint the Secretary of State, who could change the ways elections are run to gain political advantage.] How favorable of an opinion would you say you have of Doug Mastriano, or haven’t you heard enough about him?

- Wisconsin experiment: As you may know, Tim Michels is a businessman who is running as a candidate for Governor of Wisconsin in this year’s election. [Treatment language: He has expressed interest in decertifying the results from the 2020 presidential election in Wisconsin, and he continues to spread lies and conspiracy theories about that election.] How favorable of an opinion would you say you have of Tim Michels, or haven’t you heard enough about him?